So far, the collateral damage inflicted on the innocent has been given insufficient attention by those who are clamouring for a federal equivalent of the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption.

That needs to change.

The NSW experience should be closely examined to ensure the commonwealth does not follow this state’s example by adopting a system that has undermined property rights and the rule of law.

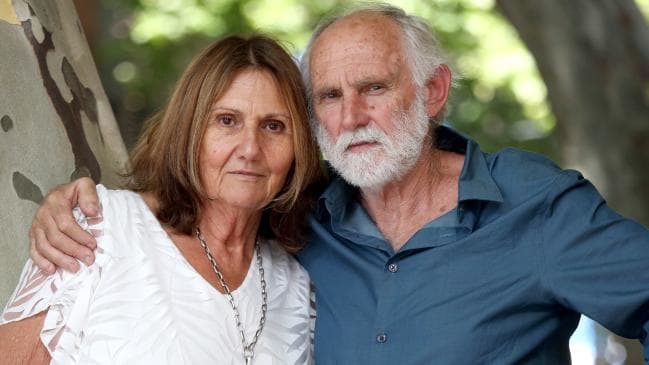

Most of those calling for a federal ICAC are almost certainly well-meaning. So before prosecuting their case any further, people of good will need to carefully consider the ICAC-related damage the state of NSW has inflicted on Warwick and Terry Howarth.

This couple has never been accused of wrongdoing. Yet the Coalition government of NSW, in the grip of an ICAC-related frenzy, passed a law that destroyed their business.

This couple had nothing to do with ICAC. Their company, Howarth Drilling, had a successful 30-year history of exploration and had business links in Australia, the US and China.

But it has been wrecked because the government of NSW, under the leadership of former premier Barry O’Farrell made a decision that paid no heed to property rights and the impact on small business.

This government refused to compensate innocent parties when it implemented an ICAC recommendation and expropriated coal exploration licences in 2014 that had been issued by the previous Labor government.

Even ICAC recognised innocent people would be hurt by this move and had recommended compensation.

One of those licences had been held by NuCoal Resources, which itself was an innocent party. NuCoal has been campaigning for years for the restoration of its lost asset.

The Howarths had a contract with NuCoal and when O’Farrell hurt this innocent mining company, the impact was also felt by NuCoal’s equally innocent contractor, Howarth Drilling.

The Howarths had bought heavy equipment worth millions dollars to complete their contractual obligations for NuCoal. When O’Farrell’s government refused to compensate NuCoal for stripping it of its asset, the decision had the effect of wrecking Howarth Drilling.

“It caused a complete meltdown of our company,” says Warwick Howarth.

“Deep hole exploration is challenging enough without being interfered with by governments.”

On the strength of its contract with NuCoal, the Howarths believed they had at least five years worth of work ahead of them. They bought four new drilling rigs at a cost of $780,000 each and had already paid for another $2 million worth of associated equipment. After the government’s decision, all work stopped and so did the company’s income.

The hurt did not end there. At the time of O’Farrell’s decision, the Howarths had 20 permanent employees, half of whom were family members. Their four children and their partners had all been part of the business.

The financial impact of the government’s decision has been catastrophic for Howarth Drilling. They had paid half the cost of the four new rigs but were dragged into court over the remaining debt and had to surrender three of them.

“We have not drilled one hole since then,” says Warwick Howarth.

The losses caused by the cancellation of NuCoal’s licence had so weakened Howarth Drilling’s balance sheet, the company has had trouble meeting the pre-tender qualifications for other work.

Warwick Howarth also suspects the link with NuCoal and the effect of the ICAC-generated licence expropriation might have had an adverse impact on his company’s standing, even though NuCoal is an innocent party.

“I could never get anyone to say that, but I believe that was a problem,” he says.

His efforts to gain some sort of compensation from the NSW government have achieved nothing, except what he describes as a bureaucratic “run-around”.

The Howarths, as well as NuCoal’s 3000 shareholders, are victims of what can only be described as legalised theft. And this is beginning to filter through to Canberra.

Centre Alliance senator Rex Patrick of South Australia recognised this when he made a remarkable statement in the senate on behalf of 184 South Australians who hold NuCoal shares.

With the benefit of parliamentary privilege, and an earlier privileged statement in the NSW Legislative Council by the Liberal Party’s Peter Phelps, Patrick sheeted home responsibility for this episode to O’Farrell, whom he accused of misleading parliament.

This extract from Hansard for November 13 tells the story.

“The NSW ICAC investigated the granting of the exploration licence and found in February 2013 that it had been granted corruptly.

“In December 2013, the NSW ICAC made recommendations that the licence be expunged and that any legislation to that effect be accompanied by a power to compensate innocent persons affected by the expunging, such as shareholders.

“In response to the ICAC investigation and recommendations, the NSW government introduced the Mining Amendment (ICAC Operations Jasper and Acacia) Act 2014.

“Significantly, the NSW parliament was never told that the ICAC had recommended that shareholders be compensated.

“Indeed, claims have been raised in the NSW Legislative Council that the parliament was deliberately told the opposite by the then premier Barry O’Farrell,” Patrick told the senate.

He drew heavily on what Phelps had said about O’Farrell in February. He had told the Legislative Council that at the time of the ICAC inquiry NuCoal had a capitalised value of $400m. After the expropriation this had been reduced to $20m.

“If the NSW parliament was deliberately misled in 2014, as has been alleged, then this is surely one of the greatest frauds in the history of that parliament — the defrauding of $400m,” Patrick told the senate.

Patrick quoted what Phelps had said in the Legislative Council: “In other words, it was a 95 per cent cut in the capital value of the company because Barry O’Farrell introduced legislation under the false claim that he was giving effect to the findings of corruption, which we now know in this instance at least, to have been substantially false, or at least highly compromised by the activities of ICAC itself.”

Because 184 innocent South Australians are among those affected by O’Farrell’s actions, Patrick and fellow South Australian senator Stirling Griff wrote to Premier Gladys Berejiklian in August seeking a remedy.

“We were particularly concerned that the legislation cancelling the licence did not implement the NSW ICAC’s recommendation to allow for the awarding of compensation to innocent parties,” Patrick told the senate.

They urged the NSW Premier to take up NuCoal’s suggestion and appoint a retired judge to examine the affair and recommend compensation for innocent shareholders.

The response, which came from a departmental official rather than Berejiklian, was pro forma: the government’s original decision had not been taken lightly and the NSW position was unchanged.

Chris Merritt

Legal Affairs Editor

The Australian

(wtf) used with permission