The extraordinary tale of Ian Macdonald has a very clear lesson: the findings of the NSW government’s anti-corruption commission are not conclusive and anyone who treats them as such does so at great risk.

The quashing of Macdonald’s conviction for misconduct in public office by the NSW Court of Appeal now stands in stark contrast with the corruption finding against this former minister that was made by the Independent Commission Against Corruption.

Those who might seek to defend this agency’s accusation against Macdonald find themselves in a difficult position. They could argue that ministerial corruption is somehow not equivalent to misconduct in public office, or they could take the equally unpersuasive route and assert that ICAC is right and five judges of the state’s highest court are not just wrong but unanimously wrong.

In these circumstances, their silence is understandable.

The Court of Appeal, while quashing Macdonald’s conviction, ordered him to face a retrial and accepted a clear reformulation of this common law offence that will govern the retrial. This is likely to have two effects.

The first is that the court’s reformulation, while based on precedent, is closely related to Macdonald’s submission and is therefore likely to improve his chances of exoneration at retrial.

The second effect is that this formulation is so favourable to Macdonald’s argument, and is backed so solidly by the appeal court, that the Director of Public Prosecutions might throw in the towel, forgoing any appeal to the High Court and declining to run a retrial.

The new approach to misconduct in public office is essentially a “but for” test that recognises that most ministerial decisions, while creating winners and losers, are not criminal offences.

The key is this: if an impugned decision would never have been made but for an illegitimate collateral effect, the law has been breached.

But if a decision would have gone ahead regardless of any collateral effect, the decision-maker is on the correct side of the law.

The options open to the prosecution have also narrowed in separate ICAC-related proceedings in which Macdonald has been charged with conspiracy to engage in misconduct in public office. That matter will also be governed by the Court of Appeal’s reformulation.

Regardless of the DPP’s decision on how to proceed, the Court of Appeal has increased the likelihood that the justice system will side with Macdonald. That would leave ICAC isolated on an issue that has devoured millions of dollars in public money, generated hundreds of headlines and fascinated NSW for years.

The issue is this: was this former mining minister engaging in misconduct when he issued a coal exploration licence in order to establish a “training mine” for coalminers that was to have been run by Doyles Creek Mining, a company chaired by former mining union leader John Maitland?

The Court of Appeal’s formulation means Macdonald will win unless the DPP can show that the training mine would never have gone ahead but for the benefit flowing to Maitland’s company.

A conclusive answer can only be provided by the courts — which is something that this affair should drive home to the politicians of NSW and parts of the media.

Instead of adhering to that principle, leading figures in politics and the media made crucial decisions based on the conceit that a government agency, untroubled by the rules of evidence and the discipline of merits appeals, had the final word.

One way or another, this affair is coming to an end in the courts. If the final answer favours Macdonald, as now seems likely, the impact on politics and the media will be immense.

Gladys Berejiklian, or whoever is premier after this month’s election, would face pressure to unwind the legislative expropriation of the Doyles Creek exploration licence that was rushed through parliament based on ICAC’s belief that the process of issuing it had been tainted by corruption.

If the courts rule on retrial there was in fact no misconduct, or the DPP declines to prosecute, ICAC’s credibility will suffer and the NuCoal expropriation will be even more insupportable.

In those circumstances, failure to restore NuCoal’s property would further infuriate the innocent shareholders whose company bought Doyles Creek Mining long after the licence had been issued.

Those shareholders include hundreds of families, particularly in the Hunter Valley of NSW, and institutional investors in the US. The Americans must now view the risk of doing business in NSW as equivalent to that of a banana republic with no respect for property rights, the rule of law or the presumption of innocence.

All of this is the direct consequence of the NSW parliament’s reliance on ICAC. It jumped the gun and took away NuCoal’s property without waiting for a conclusive assessment of Macdonald’s conduct; it made things worse by ignoring ICAC’s recommendation to compensate innocent parties who would be hurt by the expropriation.

If the DPP does throw in the towel, the consequences will be sensational. But a decision to run a retrial could be just as spectacular.

Macdonald’s star witness might well be the state’s former premier, Kristina Keneally, who is now a prominent Labor senator. Her secret evidence to ICAC — which Macdonald says favours his case — never made it into ICAC’s Acacia report to parliament.

That in itself is extraordinary: a government agency investigating ministerial corruption made no mention of a former premier’s view on appropriate ministerial conduct. Macdonald is taking legal advice on whether Keneally should be called to repeat her secret evidence. Another of those who provided secret evidence was federal Labor’s deputy leader, Anthony Albanese.

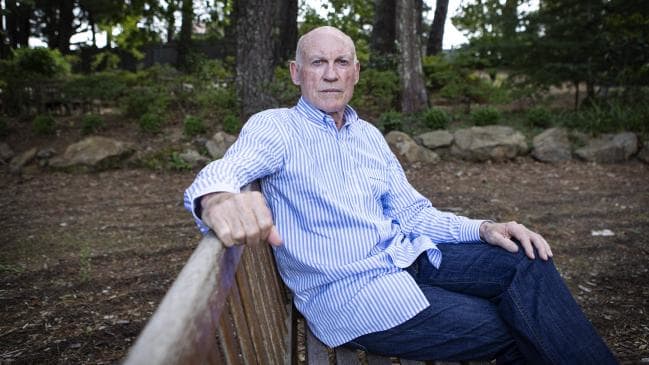

Macdonald told The Australian that over the past few years, a significant amount of information had come to light that demonstrated how witnesses before several ICAC inquiries had been denied procedural fairness.

“Core information favourable to witnesses at those inquiries was not presented,” he says.

“The problem is that the sensational nature of public inquiries and the role of the media makes it hard to defend oneself in the public arena.

“Such inquiries, if they are to be conducted, should always present information that is contrary to the narrative that is being presented in the interests of fairness and justice to witnesses.”

In his case, Macdonald says he knows ICAC had critical information that could have been explored by his legal team had it been disclosed. Much of that information emerged years after ICAC’s public hearings.

“I was charged over the training mine prior to even the DPP having access to a large volume of material taken in compulsory examinations (by ICAC) and kept away from public scrutiny,” he says.

“My lawyers found it quite extraordinary that this information had not been presented for consideration. That material was vital.

“It included interviews with Kristina Keneally which provided information that supported my position.

“In other words, the ICAC narrative which was delivered in sensationalist terms in opening addresses, failed to mention that there was substantial information given by witnesses that was directly contrary to that position and it was never furnished at the inquiry so it could be examined by my defence counsel.

“An inquiry is needed to determine why information was withheld from representatives of witnesses. How can you have a fair inquiry if you have not presented evidence that is contrary to the line being put by the agency.

“This should be assessed because public inquiries do enormous damage to witnesses. It affects their job prospects, families and friends. It affects their lives.

“I know of witnesses who have gone through the process who have virtually become hermits because of the public pressure they received during that period.

“I received quite a few insulting comments in the street generated by those public inquiries, let alone the impact it has had on my family and friends and our finances.

“In the interests of justice, not only to me but to several other witnesses before other inquiries, there needs to be a full and public assessment of the information that was not presented and why,” Macdonald says.

When ICAC sent its report on the Acacia inquiry to parliament, former commissioner David Ipp wrote: “Of course, counsel assisting and the Commission must act fairly, and reveal any material that in their view is reasonably exculpatory.”

He also wrote that: “It should be stated in clear terms that the commission is not aware of anything exculpatory in any transcript that was not the subject of evidence in the public inquiry.

“If there was credible exculpatory evidence given by a witness, the commission would expect counsel assisting to adduce it by calling that witness at the public inquiry.

“In no circumstance, to the commission’s knowledge, did counsel assisting fail to do so,” the Acacia report says.

Before he was released from prison last month by the Court of Appeal, Macdonald had been serving 10 years after being convicted by a jury in March 2017 and sentenced in May of that year. On March 8 last year, while Macdonald was still in prison, the Liberal Party’s Peter Phelps stood in the NSW Legislative Council and started reading extracts from Keneally’s secret evidence.

The Hansard record shows that ICAC counsel assisting Geoffrey Watson SC asked Keneally whether she would recall if Macdonald had taken the Doyles Creek exploration licence to cabinet.

“Possibly,” she said. “although it is a matter that would not usually come before cabinet.”

She said there would be “many circumstances” in which a minister would not take the allocation of an exploration licence to cabinet.

According to Hansard, Phelps told the NSW upper house that this extract of Keneally’s secret evidence “gives the lie to the assertion that was made in one of the final chapters of the Acacia report that they refused to release the private testimony … Because they said ‘any exculpatory evidence would have been adduced by us’.

“We now know that is a lie.”

Macdonald is still talking to his lawyers about whether Keneally and other prominent figures should be called to give evidence if a retrial goes ahead.

But he points out that “Keneally says exploration licences don’t go to cabinet, which is precisely what I have said”.

“They didn’t call Keneally, so her evidence, supportive of me, exculpatory of me, was not presented,” Macdonald says.

Chapter 33 of the Acacia report, headed “Aberrant conduct by Mr Macdonald”, lists “Mr Macdonald’s conduct in failing to refer the application to the cabinet or the cabinet budget subcommittee”. There is no suggestion that Ipp is guilty of wrongdoing.

The extraordinary tale of Ian Macdonald has a very clear lesson: the findings of the NSW government’s anti-corruption commission are not conclusive and anyone who treats them as such does so at great risk.

The quashing of Macdonald’s conviction for misconduct in public office by the NSW Court of Appeal now stands in stark contrast with the corruption finding against this former minister that was made by the Independent Commission Against Corruption.

Those who might seek to defend this agency’s accusation against Macdonald find themselves in a difficult position. They could argue that ministerial corruption is somehow not equivalent to misconduct in public office, or they could take the equally unpersuasive route and assert that ICAC is right and five judges of the state’s highest court are not just wrong but unanimously wrong.

In these circumstances, their silence is understandable.

The Court of Appeal, while quashing Macdonald’s conviction, ordered him to face a retrial and accepted a clear reformulation of this common law offence that will govern the retrial. This is likely to have two effects.

The first is that the court’s reformulation, while based on precedent, is closely related to Macdonald’s submission and is therefore likely to improve his chances of exoneration at retrial.

The second effect is that this formulation is so favourable to Macdonald’s argument, and is backed so solidly by the appeal court, that the Director of Public Prosecutions might throw in the towel, forgoing any appeal to the High Court and declining to run a retrial.

The new approach to misconduct in public office is essentially a “but for” test that recognises that most ministerial decisions, while creating winners and losers, are not criminal offences.

The key is this: if an impugned decision would never have been made but for an illegitimate collateral effect, the law has been breached.

But if a decision would have gone ahead regardless of any collateral effect, the decision-maker is on the correct side of the law.

The options open to the prosecution have also narrowed in separate ICAC-related proceedings in which Macdonald has been charged with conspiracy to engage in misconduct in public office. That matter will also be governed by the Court of Appeal’s reformulation.

Regardless of the DPP’s decision on how to proceed, the Court of Appeal has increased the likelihood that the justice system will side with Macdonald. That would leave ICAC isolated on an issue that has devoured millions of dollars in public money, generated hundreds of headlines and fascinated NSW for years.

The issue is this: was this former mining minister engaging in misconduct when he issued a coal exploration licence in order to establish a “training mine” for coalminers that was to have been run by Doyles Creek Mining, a company chaired by former mining union leader John Maitland?

The Court of Appeal’s formulation means Macdonald will win unless the DPP can show that the training mine would never have gone ahead but for the benefit flowing to Maitland’s company.

A conclusive answer can only be provided by the courts — which is something that this affair should drive home to the politicians of NSW and parts of the media.

Instead of adhering to that principle, leading figures in politics and the media made crucial decisions based on the conceit that a government agency, untroubled by the rules of evidence and the discipline of merits appeals, had the final word.

One way or another, this affair is coming to an end in the courts. If the final answer favours Macdonald, as now seems likely, the impact on politics and the media will be immense.

Gladys Berejiklian, or whoever is premier after this month’s election, would face pressure to unwind the legislative expropriation of the Doyles Creek exploration licence that was rushed through parliament based on ICAC’s belief that the process of issuing it had been tainted by corruption.

If the courts rule on retrial there was in fact no misconduct, or the DPP declines to prosecute, ICAC’s credibility will suffer and the NuCoal expropriation will be even more insupportable.

In those circumstances, failure to restore NuCoal’s property would further infuriate the innocent shareholders whose company bought Doyles Creek Mining long after the licence had been issued.

Those shareholders include hundreds of families, particularly in the Hunter Valley of NSW, and institutional investors in the US. The Americans must now view the risk of doing business in NSW as equivalent to that of a banana republic with no respect for property rights, the rule of law or the presumption of innocence.

All of this is the direct consequence of the NSW parliament’s reliance on ICAC. It jumped the gun and took away NuCoal’s property without waiting for a conclusive assessment of Macdonald’s conduct; it made things worse by ignoring ICAC’s recommendation to compensate innocent parties who would be hurt by the expropriation.

If the DPP does throw in the towel, the consequences will be sensational. But a decision to run a retrial could be just as spectacular.

Macdonald’s star witness might well be the state’s former premier, Kristina Keneally, who is now a prominent Labor senator. Her secret evidence to ICAC — which Macdonald says favours his case — never made it into ICAC’s Acacia report to parliament.

That in itself is extraordinary: a government agency investigating ministerial corruption made no mention of a former premier’s view on appropriate ministerial conduct. Macdonald is taking legal advice on whether Keneally should be called to repeat her secret evidence. Another of those who provided secret evidence was federal Labor’s deputy leader, Anthony Albanese.

Macdonald told The Australian that over the past few years, a significant amount of information had come to light that demonstrated how witnesses before several ICAC inquiries had been denied procedural fairness.

“Core information favourable to witnesses at those inquiries was not presented,” he says.

“The problem is that the sensational nature of public inquiries and the role of the media makes it hard to defend oneself in the public arena.

“Such inquiries, if they are to be conducted, should always present information that is contrary to the narrative that is being presented in the interests of fairness and justice to witnesses.”

In his case, Macdonald says he knows ICAC had critical information that could have been explored by his legal team had it been disclosed. Much of that information emerged years after ICAC’s public hearings.

“I was charged over the training mine prior to even the DPP having access to a large volume of material taken in compulsory examinations (by ICAC) and kept away from public scrutiny,” he says.

“My lawyers found it quite extraordinary that this information had not been presented for consideration. That material was vital.

“It included interviews with Kristina Keneally which provided information that supported my position.

“In other words, the ICAC narrative which was delivered in sensationalist terms in opening addresses, failed to mention that there was substantial information given by witnesses that was directly contrary to that position and it was never furnished at the inquiry so it could be examined by my defence counsel.

“An inquiry is needed to determine why information was withheld from representatives of witnesses. How can you have a fair inquiry if you have not presented evidence that is contrary to the line being put by the agency.

“This should be assessed because public inquiries do enormous damage to witnesses. It affects their job prospects, families and friends. It affects their lives.

“I know of witnesses who have gone through the process who have virtually become hermits because of the public pressure they received during that period.

“I received quite a few insulting comments in the street generated by those public inquiries, let alone the impact it has had on my family and friends and our finances.

“In the interests of justice, not only to me but to several other witnesses before other inquiries, there needs to be a full and public assessment of the information that was not presented and why,” Macdonald says.

When ICAC sent its report on the Acacia inquiry to parliament, former commissioner David Ipp wrote: “Of course, counsel assisting and the Commission must act fairly, and reveal any material that in their view is reasonably exculpatory.”

He also wrote that: “It should be stated in clear terms that the commission is not aware of anything exculpatory in any transcript that was not the subject of evidence in the public inquiry.

“If there was credible exculpatory evidence given by a witness, the commission would expect counsel assisting to adduce it by calling that witness at the public inquiry.

“In no circumstance, to the commission’s knowledge, did counsel assisting fail to do so,” the Acacia report says.

Before he was released from prison last month by the Court of Appeal, Macdonald had been serving 10 years after being convicted by a jury in March 2017 and sentenced in May of that year. On March 8 last year, while Macdonald was still in prison, the Liberal Party’s Peter Phelps stood in the NSW Legislative Council and started reading extracts from Keneally’s secret evidence.

The Hansard record shows that ICAC counsel assisting Geoffrey Watson SC asked Keneally whether she would recall if Macdonald had taken the Doyles Creek exploration licence to cabinet.

“Possibly,” she said. “although it is a matter that would not usually come before cabinet.”

She said there would be “many circumstances” in which a minister would not take the allocation of an exploration licence to cabinet.

According to Hansard, Phelps told the NSW upper house that this extract of Keneally’s secret evidence “gives the lie to the assertion that was made in one of the final chapters of the Acacia report that they refused to release the private testimony … Because they said ‘any exculpatory evidence would have been adduced by us’.

“We now know that is a lie.”

Macdonald is still talking to his lawyers about whether Keneally and other prominent figures should be called to give evidence if a retrial goes ahead.

But he points out that “Keneally says exploration licences don’t go to cabinet, which is precisely what I have said”.

“They didn’t call Keneally, so her evidence, supportive of me, exculpatory of me, was not presented,” Macdonald says.

Chapter 33 of the Acacia report, headed “Aberrant conduct by Mr Macdonald”, lists “Mr Macdonald’s conduct in failing to refer the application to the cabinet or the cabinet budget subcommittee”. There is no suggestion that Ipp is guilty of wrongdoing.

Chris Merritt, Legal Affairs Editor

The Australian

WTF (used with permission)