Last month, when Richard Poole told his appalling story to a committee of the NSW parliament, he faltered, apparently close to tears. After what happened to him at the hands of the state’s anti-corruption commission, and the impact it had on his children, the politicians in that hearing room seemed moved.

“It is OK. You can take a moment,” said the Liberal Party’s Tanya Davies, who chairs an inquiry into the reputational impact of being adversely named by the Independent Commission Against Corruption.

To understand Poole’s plight, keep in mind that he is an innocent man. He has been convicted of nothing and until a court rules otherwise, he is entitled to the respect due to all those who adhere to the law.

Yet this is how he described the impact of being declared corrupt by ICAC, a body that is frequently mistaken for a court:

“It is something I would not wish on my worst enemy … I have four boys — at the time my boys were all at school,” Poole told the inquiry.

“Fundamentally, they had to walk into school and they would be asked, ‘Is your dad going to jail? Your dad’s a crook. Your dad’s a thief’.”

The presumption of innocence is not a technicality. It is fundamental to the rule of law and gives meaning to the assertion of freedom in the national anthem.

The federal government’s booklet that helps new arrivals prepare for the citizenship test says this: “Australians are equal under the law. The rule of law means that no person, group or religious rule is above the law. Everyone, including people who hold positions of power in the Australian community, must obey Australia’s laws. This includes government, community and religious leaders, as well as business people and the police.”

This was once true. But in NSW an act of parliament has exempted ICAC, a government agency, from the consequences of breaching the law as expounded by the High Court.

Poole has won decisions in his favour from the NSW Director of Public Prosecutions and the full Federal Court but ICAC’s accusation of corruption is still on the books despite the fact that ICAC itself has accepted it is invalid.

That concession is outlined in a letter from the NSW Crown Solicitor’s office dated April 23, 2015, and is signed by senior solicitor Aaron Baril.

It was triggered by an unrelated High Court victory by Sydney silk Margaret Cunneen SC that meant the commission had been acting without authority in several matters, including Poole’s case. Its actions had no basis in law and were therefore unlawful.

When statutory bodies inflict unlawful damage, those responsible should be identified and, if necessary, replaced to ensure there can be no repeat. Remedies should be provided to their victims.

That is what should have happened in 2015. But when ICAC’s unlawful conduct came to light, the government of former premier Mike Baird did the reverse. With support from the Labor opposition, Baird passed a law that retrospectively validated ICAC’s invalid actions. This law-breaking agency was protected.

To make matters worse, the Independent Commission Against Corruption Amendment (Validation) Act cut across moves by former Court of Appeal president Margaret Beazley who had prepared a draft declaration, at the request of the affected parties, that would have stated that ICAC had no jurisdiction to declare them corrupt.

Poole deserves a remedy not merely because ICAC exceeded its powers, but because the justice system, after examining his conduct, found no wrongdoing.

In July 2013, ICAC referred him for possible prosecution. The DPP then considered what to do for almost seven years. Yes, you read that right. The DPP took almost seven years to make a decision.

The DPP has had a unit to consider prosecutions arising from ICAC inquiries since 2013. In 2017-18 it had seven lawyers and a support officer, according to the DPP’s annual report. On Wednesday, the DPP was asked what factors might explain the delay. No response has been received. It was only on March 26 last year that ICAC informed Poole’s lawyers that advice had been received from the DPP on March 24 that ICAC’s evidence was insufficient to justify a prosecution.

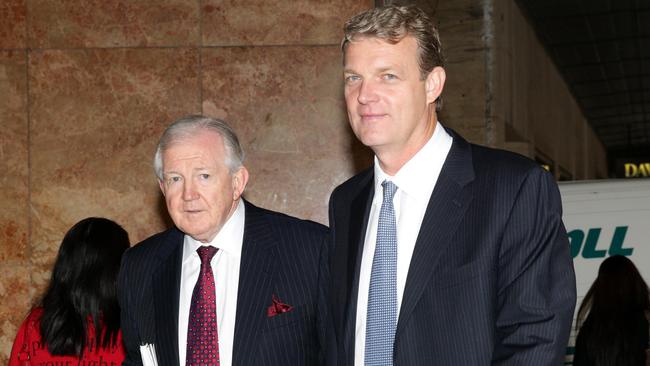

A year earlier, the full Federal Court unanimously threw out cartel conduct proceedings against Poole and fellow directors of mining company Cascade Coal that originated in accusations at an ICAC inquiry known as Operation Jasper.

The Validation Act means Poole, while innocent, is unable to remove the taint imposed unlawfully by ICAC. The injustice is blatant and inexcusable. This might explain why Labor’s Adam Searle took care to confirm the key elements:

Searle: In those matters, ICAC agreed that, on the basis of the Cunneen ruling, its findings could not be sustained. Is that correct?

Poole: Yes.

Searle: And the court essentially agreed to enter those orders by consent. Is that correct?

Poole: Yes.

Searle: But before the court was able to do that, parliament enacted the validation legislation to retrospectively validate.

Poole: Correct.

Searle: And it was that act of the parliament that took your crystallised legal rights away from you two days before they were about to be given.

Poole: Yes.

Nothing can fully compensate for the great wrong inflicted on this innocent man and his children. Instead of attacking corruption, NSW corrupted the rule of law to appease wrongdoers.

Poole’s rights must be restored and that means the Validation Act must go.

Chris Merritt is vice-president of the Rule of Law Institute of Australia. For Australia Day, the institute is preparing free information packs on the core democratic beliefs outlined in the government’s citizenship booklet. That material is available next week from the institute’s website.